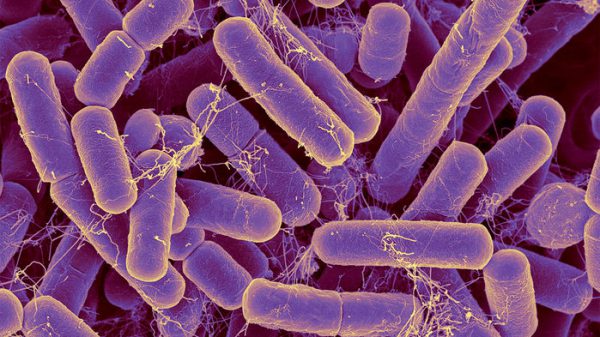

The billions of bacteria that call your gut home may help regulate everything from your ability to digest food to how your immune system functions.

The billions of bacteria that call your gut home may help regulate everything from your ability to digest food to how your immune system functions.

Biological clock

But scientists know very little of how that system, known as the microbiome, changes over time—or even what a “normal” one looks like. Now, researchers studying the gut bacteria of thousands of people around the globe have come to one conclusion: The microbiome is a surprisingly accurate biological clock, able to predict the age of most people within years.

To discover how the microbiome changes over time, longevity researcher Alex Zhavoronkov and colleagues at InSilico Medicine, a Rockville, Maryland–based artificial intelligence startup, examined more than 3600 samples of gut bacteria from 1165 healthy individuals living across the globe. Of the samples, about a third were from people aged 20 to 39, another third were from people aged 40 to 59, and the final third were from people aged 60 to 90.

Machine learning

The scientists then used machine learning to analyze the data. First, they trained their computer program—a deep learning algorithm loosely modeled on how neurons work in the brain—on 95 different species of bacteria from 90% of the samples, along with the ages of the people they had come from. Then, they asked the algorithm to predict the ages of the people who provided the remaining 10%. Their program was able to accurately predict someone’s age within 4 years, they report on the preprint server bioRxiv. Out of the 95 species of bacteria, 39 were found to be most important in predicting age.

Zhavoronkov says this “microbiome aging clock” could be used as a baseline to test how fast or slow a person’s gut is aging and whether things like alcohol, antibiotics, probiotics, or diet have any effect on longevity. It could also be used to compare healthy people with those who have certain diseases, like Alzheimer’s, to see whether their microbiomes deviate from the norm.

The length of telomeres

If the idea is validated, it would join other biomarkers scientists use to predict biological age, including the length of telomeres—the tips of chromosomes implicated in aging—and changes to DNA expression over a person’s lifetime. Combining the new aging clock with these others could yield a much more accurate picture of a person’s true biological age—and health. It could also help researchers better test whether certain interventions—including drugs and other treatments—have any effect on the aging process. “You don’t need to wait until people die to conduct longevity experiments,” Zhavoronkov says.

The idea that you can predict someone’s age based on their gut microbiome is “very plausible” and of “tremendous interest” to scientists studying aging, says computer scientist and microbiome researcher Robin Knight, director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation at the University of California, San Diego. His group is analyzing 15,000 samples from the American Gut Project, a worldwide microbiome study he founded, to develop similar age predictors.

But one of the challenges of developing such a clock, he adds, is that there are huge differences in which bacteria are present in the guts of people around the world. “It’s extremely important to replicate these kinds of studies with markedly different populations” to find out whether there are distinct signs of aging in different groups of people, Knight says.

He says it’s also not known whether changes in the microbiome cause people to age more rapidly, or whether the changes are simply a side effect of aging. InSilico Medicine is building several aging clocks based on machine learning that could be combined with the microbiome one. “Age is such an important parameter in all kinds of diseases,” Zhavoronkov says. “Every second we change.”